Abba Piamun of Diolcos

Welcome to the series on the Desert Fathers! If you are just joining us on this journey through the Desert Fathers, please refer back to my initial letter The Desert Fathers; An Introduction explaining the goal and purpose of this series.

“True patience and tranquility is neither gained nor retained without profound humility of heart.”

Who was Abba Piamun of Diolcos?

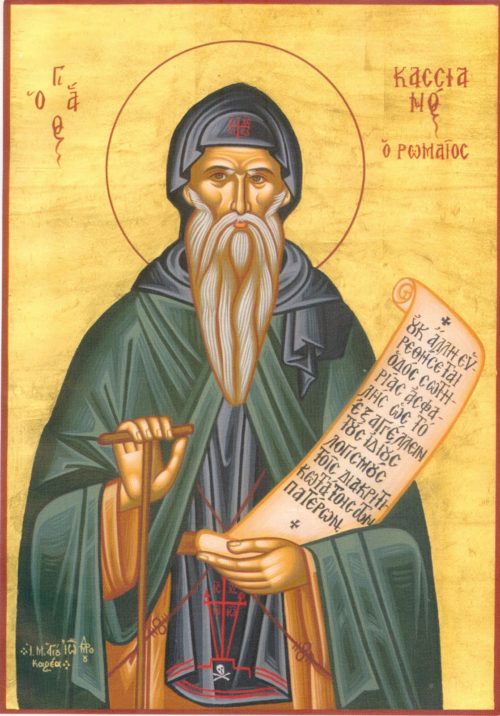

The teachings of Abba Piamun of Diolcos were recorded by John Cassian, a monk who traveled through the monastic regions of northern Egypt near the end of the 4th century. Cassian traveled extensively and recorded the teachings of various Desert Fathers in order to spread the teaching of monasticism from the east to the west.

Piamun was the overseer of a large group of monks known as a “larger and more perfect company of saints.” The reputation of the community of Piamun had spread wide, attracting men like Cassian to learn from him and the others within the community he oversaw. The community was located near the mouth of the Nile, on a mountain outside of the village of Diolcos in Northern Egypt.

Piamun did not seek fame and recognition. Once, when presented with some grapes and wine offered by a brother he preferred to taste the gifts rather than abstain as was his normal practice. He knew that if he abstained the brother would exalt the discipline of the father. Piamun would rather honor the generosity of the brother and hide his practice in humility.

This is a constant refrain of the desert fathers and mothers. They were more concerned with hiding the deeds they have worked rather than lauding their accomplishments in the open. A good deed hidden becomes a seed buried deep in the heart that works the precious virtue of humility in the depth of the person. In this way the seed comes from the fruit of intimacy rather than the desire to be known or recognized.

Monastic Life

According to Abba Piamun, there were two types of monks, those that are called Coenobites, and those that are called Anchorites. Coenobites were by far the most common expression of those who embraced monastic living throughout Egypt.

“The first is that of the Coenobites, who live together in a congregation and are governed by the direction of a single Elder: and of this kind there is the largest number of monks dwelling throughout the whole of Egypt.”

The predominant mark of a monk was his desire to submit his life to the leading of another. In doing this, the one living alone for Christ practiced the declaration of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane, “Not my will, but yours be done.”

Piamun traced Coenobitic living back to the days of the book of Acts, claiming this type of monastic living was a fulfillment of the statement in Acts:

“But the multitude of believers was of one heart and one soul, neither said any of them that any of the things which he possessed was his own, but they had all things common. They sold their possessions and property and divided them to all, as any man had need.”

The role of the Coenobite was to practice common unity. Submission and humility were ways of life for these monastics. They dwelt together in beautiful simplicity, submitted one to another:

“…a Coenobium cannot be spoken of except where dwells a united community of a large number of men living together.”

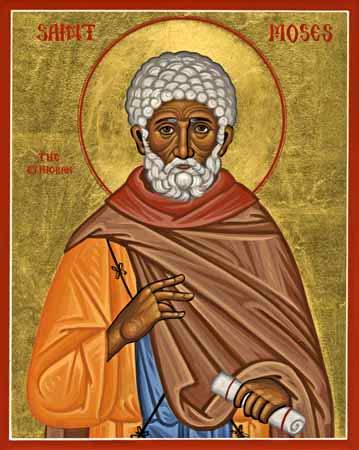

The second class of monks, the Anchorites, arose as the most perfect of those living in submission to the community. An anchorite was the spiritually mature monk who took the example of John the Baptist, Elijah, and Elisha as their inspiration. Having risen to excellence in the midst of the Coenobitic community, the anchorite would withdraw (the term anchorite means “withdrawer”) to the recesses of the desert in order to engage in intense spiritual warfare. This warfare was the battle of the heart. The anchorite spent his time engaged in prayer, fasting, and spiritual discipline in order to conquer the darkness in his own heart.

The anchorites were…

“men who frequented the recesses of the desert, not as some from faintheartedness, and the evil of impatience, but from a desire for loftier heights of perfection and divine contemplation.”

They did not remove themselves from the Coenobitic monastery out of frustration with other monks, but rather out of the excellence of their lives they desired to dive deeper into the heart of God. To them, perfect stillness and perfect solitude were required to know God in the deepest places of the heart.

Piamun named a number of other classes of monasteries, but claimed they were of a lesser class. He cautioned his disciples against joining a monastic order that did not require submission to a spiritual father. To Piamun, how could you practice the spiritual life if at the outset you sought to fulfill your own will?

The Spiritual Life

In order to grow in any skill or art we must practice that skill or art. Without the effort we will never see the desired result. Abba Paimun said to Cassian:

“Whatever man, my children, is desirous to attain skill in any art, unless he gives himself up with the utmost pains and carefulness to the study of that system which he is anxious to learn, and observes the rules and orders of the best masters of that work or science, is indulging in a vain hope to reach by idle wishes any similarity to those whose pains and diligence he avoids copying.”

Without the effort there will be no growth, it will merely be vain hope. To grow in the depths desired, it takes learning from those who have gone before, the “masters of that work.”

In order to do this, we will have to unlearn what we have learned.

“Wherefore if, as we believe, the cause of God has drawn you to try to copy our knowledge, you must utterly ignore all the rules by which your early beginnings were trained, and must with all humility follow whatever you see our Elders do or teach.”

If the previous foundation that was laid was faulty, it stands to reason that we have to question the principles of that foundation. When it comes to the spiritual life, what we practice is of the utmost important. The healthier the food consumed the greater the health of the spiritual life.

It was imperative to Piamun that what was taught was also practiced. He said,

“…the knowledge of all things will follow through experience of the work. But he will never enter into the reason of the truth, who begins to learn by discussion…”

To learn and not practice would leave the person in serious danger of error. Learning leaves knowledge up to the judgement of the person, practice dives into the experience and teaches the path to true knowledge in the depths of the heart of God. Discussion without practice leaves the monastic overfed and under-practiced.

Humility

Abba Piamun taught that humility was the foundational principle of the spiritual life. Without humility there could be no depth of prayer, without depth of prayer there can be depth of spirit, without depth of spirit there can be no true knowledge of God in the heart.

“True patience and tranquility is neither gained nor retained without profound humility of heart…”

True peace of heart is not anchored in solitude and silence, but rather in the practice of humility. The desert is not the avenue to patience and tranquility, but rather the practice of humility.

“…true humility of heart must be preserved, which comes not from an affected humbling of body and in word, but from an inward humbling of the soul.”

This humility is gentleness of spirit when wronged…

“…when another insolently accuses him of them (sin), thinks nothing of it, and when with gentle equanimity of spirit he puts up with wrongs offered to him.”

Insults, accusations, and conflicts serve a greater purpose in the spiritual life.

“But if we are disturbed when attacked by anyone it is clear that the foundations of humility have not been securely laid in us.”

The offense taken demonstrates the lack of maturity. Every wrong committed against us has the potential to mature us, if we allow it to. Without the proper response of humility it will just become another circumstance, rather than a profound lesson on humility.

“When then anyone is overcome by a wrong, and blazes up in a fire of anger, we should not hold that the bitterness of the insult offered to him is the cause of his sin, but rather the manifestation of secret weakness…”

The weakness being this: the foundation that our heart rests upon, either sand or stone, as in the parable of Jesus.

Speaking about Abba Paphnutius, Piamun said,

“But because the holy servant of God had fixed the hope of his heart not on those external things but on Him Who is the judge of all secrets, he could not be moved even by the machinations of such an assault as that.”

The test of whether his hope was set on God or not was seen in the assaults of others on his character. If he was moved by their negative words his heart lacked rest in the peace of God. Isaiah 26:3 states that the mind set on God will be at perfect peace. If you lack peace in the depths of the heart in the midst of difficult circumstances, it is not a reflection on the inefficiency of God’s peace but on the state of your heart. Reproach shows us where our heart refuses to anchor itself in God’s peace. Humility leads to patience, and patience to peace, and peace to God.

Patience is tested by what happens to us.

“For everybody knows that patience gets its name from the passions and endurance, and so it is clear that no one can be called patient but one who bears without annoyance all the indignities offered to him, and so it is not without reason that he is praised by Solomon: “Better is the patient man than the strong, and he who restrains his anger than he who takes a city…”

Just ask anyone who has ever prayed, “God, help me to be more patient.”

Without conquering the heart and subduing the will we have no hope.

“For just as “the kingdom of God is within you,” so “a man’s foes are they of his own household.” For no one is more my enemy than my own heart which is truly the one of my household closest to me.”

The state of our heart is our own worst enemy.

“…if I am injured, the fault is not owing to the other’s attack, but to my own impatience.”

Abba Piamun leaves us with no small task. In order to fully enter into the depths of our heart and encounter the presence of God within we must deal with what would rob us of peace. To Piamun this was the path to purity, and coupled with submission to a spiritual father, it would lead us to God.